Among the non-trophoblastic, benign placental tumors, the chorioangioma is the most common, accounting for 1% of the overall total (Yadav et al, 2017; Kurman et al, 2019). Although most chorioangiomas have no clinical repercussions, they may conjoin in the development of polyhydramnios, premature birth, preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, platelet entrapment, arteriovenous short circuit, maternal mirror syndrome (maternal edema or pre-eclampsia with hydrops fetalis), stillbirth (Heerema-McKenney, 2019), non-reassuring fetal status, fetal anemia, cardiomegaly (Wu and Hu, 2016) and neonatal death; however, chorioangiomas rarely result in postpartum bleeding (Kramer et al, 2011). This article presents the case of a patient with postpartum uterine atony that required hysterectomy, with subsequent histopathological confirmation of a giant chorioangioma.

Clinical case

A 35-year-old patient was undergoing routine prenatal checkup at gestational week 35, with suspicion of preterm delivery as a result of advanced stage labor contractions. The patient had a history of three pregnancies, one live birth and one miscarriage. The patient suffered from hypertension (142/85 mmHg) linked to urine protein:creatinine ratio of 0.26, with no evidence of target organ damage. Following vaginal delivery, uterine examination revealed placental remnants suggestive of uterine wall infiltration with subsequent uterine atony and 1000 cc blood loss that triggered a code red alert. The patient did not respond to doses of oxytocin, methergine and tranexamic acid; because of the suspicion of placenta accreta, the patient underwent total abdominal hysterectomy. Table 1 contains the paraclinical case data.

Table 1. Patient paraclinical data collected at initial admittance, pre-delivery and immediately post-delivery

| Paraclinical features | Day 1 | Day 2 | Reference ranges | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At admittance | At 6 hours postoperative | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.2 | 9.4 | 7.3 | 12.5–16 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 37.4 | 28.1 | 21 | 37–47 |

| Platelets (uL) | 175 | 103/150–450 | ||

| Prothrombin time (seconds) | 10.6 | 12.3 | 11.8 | |

| Thromboplastin time (seconds) | 27.2 | 35.5 | 30.6 | |

| Fibrinogen mg/dl | 430 | 326 | 220–500 | |

| Lactic acid mmol/l | 4.1 | 0.5–2.2 |

Patient hospital discharge took place following blood transfusion; on postpartum day 9, patient reported severe migraine and hypertension (160/78 mmHg), and adequate treatment with magnesium sulphate and labetalol followed.

The male newborn had a Ballard score of week 38, Apgar score of 8 at 1 minute and 9 at 5 minutes, birth weight of 2940 g and length of 49 cm. He had no birth defects, specifically no vascular lesions, no neonatal complications and was healthy at discharge.

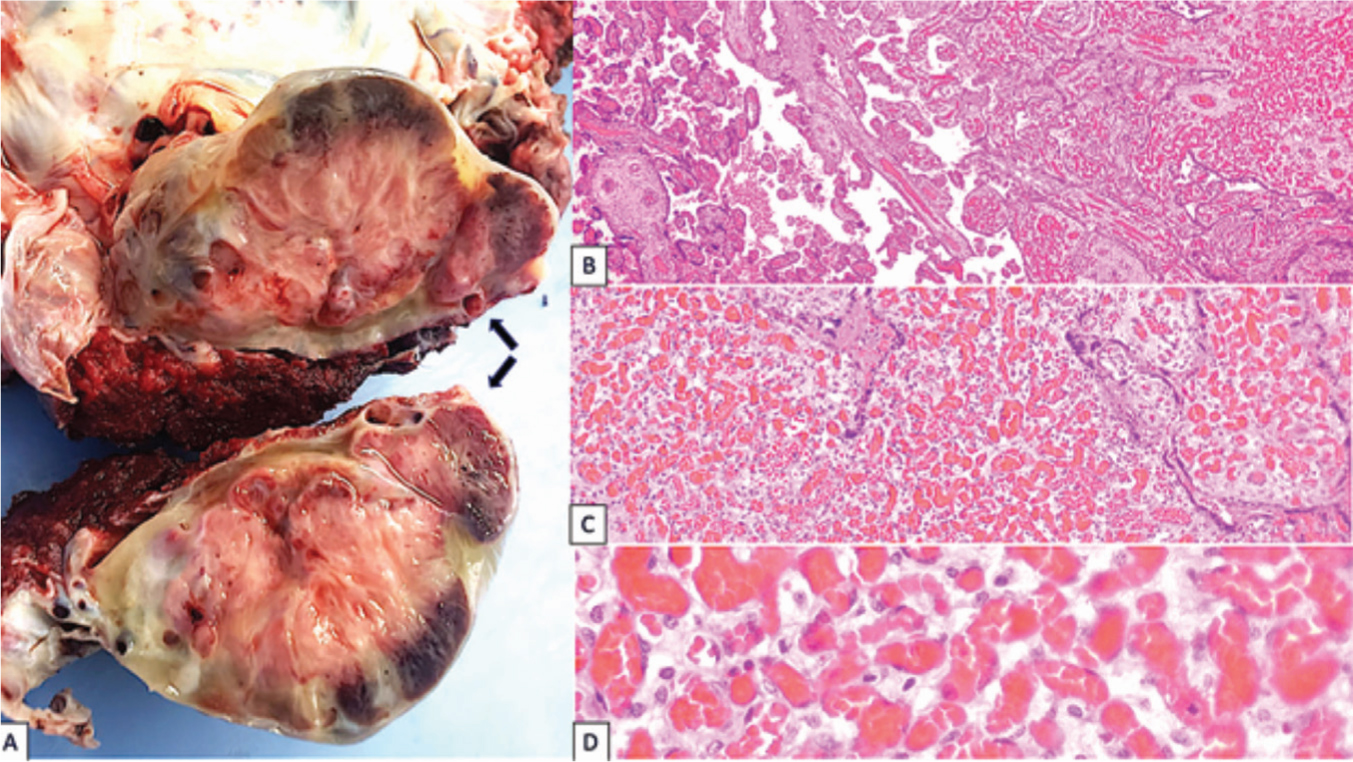

The pathology lab reported an 833 g placenta, measuring 16×12 cm, with a heterogeneous 6.5×4.5×4 cm lobulated mass under the amnion that pointed toward fetal face (Figure 1A). No other macroscopic lesions, such as fibrin deposits, infarcts or others, were found. Histological classification was chorioangioma, whose outstanding feature is an abundance of capillaries with apparently mature endothelia (Figure 1). Additional histopathologic features included fetal vascular malperfusion (maternal villous vessel obliteration and thrombosis), perivillous fibrin deposits and circulating normoblasts. However, there were no umbilical cord malformations and no indication of placenta accreta in the uterus.

Figure 1. a) Macroscopic chorioangioma features (arrows): uutlined mass, yellowish color of 6.5×4.5×4 cm in its major diameters b) Microscopic chorioangioma features: transition between chorial villi (left) and chorioangioma (right). H&E staining, 4× c) Chorioangioma: predominant capillary proliferation. H&E staining, 10× d) Chorioangioma: Relaxed endothelium capillaries. H&E staining, 40×

Figure 1. a) Macroscopic chorioangioma features (arrows): uutlined mass, yellowish color of 6.5×4.5×4 cm in its major diameters b) Microscopic chorioangioma features: transition between chorial villi (left) and chorioangioma (right). H&E staining, 4× c) Chorioangioma: predominant capillary proliferation. H&E staining, 10× d) Chorioangioma: Relaxed endothelium capillaries. H&E staining, 40×

Ultrasound images before and after histological diagnosis showed no tumor or mass.

Discussion

The term postpartum vaginal haemorrhage signifies blood loss in excess of 500 ml in vaginal delivery (1000 ml for caesarean section) (Buca et al, 2020), as well as other clinical parameters such as low body mass index, severe anaemia and other causes of hemodynamic instability (Arulkumaran and Doumouchtsis, 2016). Postpartum haemorrhage is the third most common cause of maternal death in the world and is usually associated with hypotonia, genital trauma, retained placenta, coagulopathy (disseminated intravascular coagulation resulting from massive bleeding, placental abruption, sepsis, preeclampsia or primary coagulation disorders) or infection (Arulkumaran and Doumouchtsis, 2016). The literature rarely describes the association of chorioangioma to postpartum hemorrhage or uterine atony (Kramer et al, 2011).

A chorioangioma or placental hemangioma is a predominantly asymptomatic (80%), benign vascular tumor with an incidence rate between 1:8000 and 1:50000 cases (Singh et al, 2021). If it measures over 4 cm in length, it is a ‘large’ tumor and can be a factor in the manifestation of fetal and maternal complications (Heerema-McKenney, 2019). Conditions associated with tumor appearance include twin births, female fetus, mother over age 30 years, hypertension, diabetes, first pregnancy and previous chorioangioma (Heerema-McKenney, 2019). The advanced-age patient described in this case study had hypertension.

Chorioangiomas can cause multiple vascular malformations that in turn can bring about arteriovenous short circuits, affecting fetal hemodynamic status through platelet and red blood cell sequestration. Another reported adverse chorioangioma-related effect on the fetus is the creation of polyhydramnios (10–28%), a phenomena that can either be attributed to tumor proximity to cord insertion that produces mechanical compression on the umbilical vein and consequent hydrostatic pressure or to the tumor itself applying vascular pressure upon the amniotic cavity (Álvarez et al, 2021). Additional studies implicate chorioangiomas in the increase of fetal urine output because of a hyperdynamic circulatory state (Liu et al, 2014). Chorioangiomas can also produce fetal microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, brought about by the mechanical fragmentation and the destruction of red blood cells as they pass through tumor short circuits and vasculature. Chorioangioma links to intrauterine growth restriction involve short circuits created by preferential derivation toward the low-pressure system of the tumor, which limits nutrient and oxygen intake to the fetus (Liu et al, 2014). Ultimately, large tumor size is the major contributing factor linked to fetal complications (Heerema-McKenney, 2019; Buca et al, 2020). If a chorioangioma measures less than 4 cm in length, complications occur in 44% of cases; chorioangiomas of over 4 cm produce complications in 100% of cases, including a 28% perinatal death rate (Al Wattar et al, 2014). Cardiac insufficiency, including disseminated intravascular coagulation, hydrops fetalis and tachycardia, is the main cause of fetal death (Heereema-McKenney, 2019). Cutaneous hemangiomas (especially in cases of multiple chorioangiomas) may appear on over 50% of a newborn's skin (Heerema-McKenney, 2019).

Mater nal complications linked to large chorioangiomas include preterm delivery, gestational hypertensive disorder, proteinuria, thrombocytopenia, pre- and post-delivery haemorrhage, placenta retention, caesarean section, mirror syndrome, placenta abruption, placenta praevia, velamentous insertion of the placenta and breech presentation. The associated risk of chorioangioma remains even after accounting for preterm delivery control (Dong et al, 2020).

Prenatal diagnosis based on ultrasound imaging generally takes place in second and third gestational quarters. A typical image reveals a subchorionic mass, whose echogenicity differs from that of the placenta, turned toward the fetal face, near umbilical cord insertion. Doppler imaging reveals abundant liquid flow and vasculature. Concomitantly, signs of intrauterine growth restriction and fetal anemia may appear. It is important to point out that there is a link between tumor vasculature channel and umbilical cord pulsations, which suggests continuity of fetal circulation with the chorioangioma. This finding aids in reaching a differential diagnosis. No abnormalities appeared in the routine ultrasound exam for the case discussed in this article.

Examination of the placenta may show the mass localised inside the placenta or connected to it by a pedicle (Kurman et al, 2019). Masses tend to be firm and brownish-red or yellow in color with well-defined borders that may diffusely involve the placenta. In the case described in this article, the subchorial localised mass was intraparenchymal and heterogeneous, brownish-yellow in color and had no pedicle.

Histological studies show chorioangiomas to be vascular tumors created by the abnormal proliferation of angioblasts and fibroblasts, overlaid with trophoblast attenuation or hyperplastic tissue (Heerema-McKenney, 2019). They may have myxoid change, necrosis or calcification (Kurman et al, 2019). There are also reports of the presence of abundant or atypical mitosis, which in no way affect biological behavior (Vellone et al, 2015). Current histological research places emphasis on possible stromal predominance and probable presence of hemorrhagic infarction or ischemic necrosis (Redline, 2018). Classical Marchetti's classification (angiomatous (capillary), cellular and degenerative) has no clinical implications and receives no mention, nowadays.

Differential diagnosis should be made with chorangiosis and chorangiomatosis. In the first, there is an increased number of capillaries: more than 10 capillaries per villus in 10 or more distal villi in several regions of the placenta (Redline, 2018). In multifocal chorangiomatosis, there is a network of small anastomosing vessels at the margins of stem and intermediate villi and the lesion lacks circumscription (Redline, 2018; Heerema-McKenney, 2019).

Misdiagnosis most often occurs because of mistaken identification of chorangiomas surrounded by proliferative trophoblasts as being instead intraplacental chorangiocarcinoma (Redline, 2018; Heerema-McKenney, 2019).

The use of the immunohistochemial marker human glucose transporter protein-1 is highly effective in identifying juvenile hemangiomas in any organ (Silva et al, 2015). Capillaries in chorioangiomas test positive to this marker and it requires no genetic study. There are other vascular markers, such as CD31, CD34 and factor VIII, which stain in the capillaries (Kataria et al, 2016). Focal expression of cytokeratin also occurs in this lesion (Theresia et al, 2021). Immunohistochemistry is not required for diagnosis (Heerema-McKenney, 2019). Differential histological diagnoses made possible by use of this marker include focal chorangiosis, multifocal chorioangiomatosis and chorangiocarcinoma (Heerema-McKenney, 2019). The karyotype tends to be normal; and clonality does not occur (Heerema-McKenney, 2019).

Chorioangioma management is especially challenging, and knowledge of pre-natal complications is essential to an individualised-care approach.

In this case study, there were no prenatal suspicions; postpartum bleeding occurred accompanied by uterine atony that required hysterectomy. This type of condition is unusual, corresponding to only 0.26% in a cohort of 10 3726 patients who suffered from postpartum haemorrhage, 19.7% of whom experienced acute postpartum haemorrhage (Kramer et al, 2011).

Chorioangioma is a histologic benign lesion, but despite this, it can be lethal. It may produce immediate harmful side effects for both mother and fetus, as well as impact long-term neurological development in cases of interrupted blood flow. Although prenatal diagnosis is possible, definitive histologic analysis of the placenta in specific cases, such as that outlined in this article, allows for precise lesion identification (Khong et al, 2016).

Key points

- Placenta abnormalities may cause postpartum bleeding.

- Chorioangiomas are not always evident in prenatal ultrasound imaging.

- Chorioangiomas could be accompanied by hemangiomas in the newborn.

- A giant chorioangioma may be a hazardous for both mother and child.

CPD reflective questions

- Under what circumstances should the pathology lab examine the placenta?

- Why do the chorioangiomas and the newborn's hemangiomas test positive for the same antibodies?

- What are the possible implications of a giant chorioangiomas in the newborn?

- What are the possible implications of a giant chorioangiomas in the mother?

- What are the pre and postpartum suspect signs of chorioangiomas?